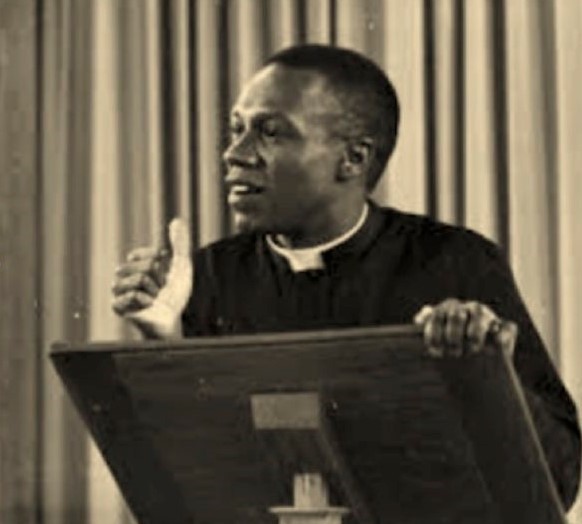

I remember Jerry Ringer so handsome in high school. He went to the all-boys Catholic high school and I to the all-girls. We were on stage together in Shakespeare plays – Romeo and Juliet, Julius Cesar — and contemporary American comedies like The Man Who Came to Dinner. The plays were directed by Fr. Clarence Joseph Rivers — a small-built person of prodigious energy, an African American priest, a musician who brought guitar music to the Catholic Mass, and a lover of language. It goes without saying, Fr. Rivers endured racism but not from us kids. He called our theatre group the Queen’s Men, after Shakespeare’s company, and through laughter and patience he taught us to enunciate, navigate, appreciate, and perform Shakespearean verse.

After I graduated high school and left home for college, I lost touch with Fr. Rivers and the Queen’s Men — except for handsome Jerry Ringer. Like the other Queen’s Men, Jerry stayed in Cincinnati but not to attend university or work for Procter & Gamble, but to create the life of an artist. He was the true bohemian among us. Home for spring break my sophomore year, I called Jerry and left a message. He called me back from a phone booth. He said, they discovered a hole in his heart on Valentine’s Day and there’d be surgery. I imagined him in a black trench coat with the collar turned up leaning against the inside door of the phone booth. He said he hadn’t known, but his heart was broken all along. I felt like I could love this boy, and then the next thing I knew, he was dead.

That’s one of the prospects now with the virus of various names: Corona-19, SARS-CoV-2, Novel Coronavirus, COVID. I could be talking on the phone to someone and then –. I’m not imagining a specific person, just someone old, and anyway it’s an unthinkable imagining. Or, it could be the other way — someone talking to me on the phone and then –. When I first heard the name Corona, I thought it had to do with coronary, that one’s heart gives out. But, in fact, it’s the lungs that are affected, though now we know it can travel to the heart, and it doesn’t help in the first place to have a heart full of trouble.

The scope of the virus and the multitude of human beings it’s direly infecting brings to mind the truth of impermanence: Everything changes, nothing lasts, everybody dies. Most of us infrequently contemplate the truth of impermanence. But working in the theatre brings the truth of impermanence home show after show. Early on in my career at Villanova Theatre, there was a technical director, John Parmalee, responsible for getting the sets built according to design plans. John was a capable TD as well as a soft-spoken, gentle person. When a show was over and it was time for the set to come down, as per the event known as “strike,” John would singlehandedly initiate the destruction of the set, just to get things started. He’d wield a hammer, and wham, that’s how the strike began. He once told me strike was his favorite part of the job. I protested, “But you built the set!” He liked the understanding that the theatre and all its scenery isn’t supposed to last.

I didn’t like to attend the strikes of productions I’d directed. It felt shocking to me: hardly an hour from a show closing to the first blow. Like with handsome Jerry Ringer – a promising phone call and then silence. That’s the theatre — it hardly gets going and it’s over. In that sense, the theatre is a generous teacher of dharma or the truth of how things are. Every day is new on stage. No performance can possibly stay quite exactly the same. Nothing lasts beyond the curtain. Every show goes to strike. And all the characters are no more.