The Memorial Day weekend front page of The Sunday New York Times will not soon be forgotten. The page is printed entirely with names of persons taken by Coronavirus. Each entry includes the person’s age and hometown, and a line signifying something of who they were. There was Lila A. Fenwick, 87, New York City, first black woman to graduate from Harvard Law School; Timothy Branscomb, 32, Chicago, always busy looking out for others; Marty Derer, 56, New Jersey, loved to referee basketball games; Hailey Herrera, 25, New York City, budding therapist with a gift for empathy. Totaling 1000, the names continue on for two more pages of the newspaper, making 1/10th of the 100,000 persons lost to Covid19 here in the US. It’s impossible to read any 10 of the names and not weep.

The page is a work of minimalist art and dramatic. It’s also an invitation to compassion – not as an idea but as a feeling, as an aching — the ache of loss, arising somewhere in the chest, because we’re willing to share other people’s suffering.

The page brought to mind a production of Waiting for Godot I directed in 2001, where I had the idea to cover the entire back wall of the set, floor to ceiling, with newsprint. With the audience on 3 sides of the stage, everyone could see, though couldn’t read, the writing. During one of his exchanges with Estragon, Vladimir (played by Jared Delaney) went to the back wall and stood facing the vast expanse of newsprint, just looking and listening, during these lines:

Vladimir: You’re right, we’re inexhaustible.…

Estragon: It’s so we won’t hear.

Vladimir: We have our reasons.

Estragon: All the dead voices.

Vladimir: They make a noise like wings.

Estragon: Like leaves.

Vladimir: Like sand.

Estragon: Like leaves.

Silence.

Vladimir: They all speak at once.

Estragon: Each one to itself.

Silence.

Vladimir: Rather they whisper.

Estragon: They rustle.

Vladimir: They murmur.

Estragon: They rustle.

Silence.

Vladimir: What do they say?

Estragon: They talk about their lives.

Vladimir: To have lived is not enough for them.

Estragon: It is not sufficient.

Silence.

Vladimir: They make a noise like feathers.

Estragon: Like leaves.

Vladimir: Like ashes.

Estragon: Like leaves.

Long silence.

The Memorial Day 2020 Sunday New York Times manages to speak the lives of the whispering dead, who, until then, had not been heard of publicly and surely not heard from.

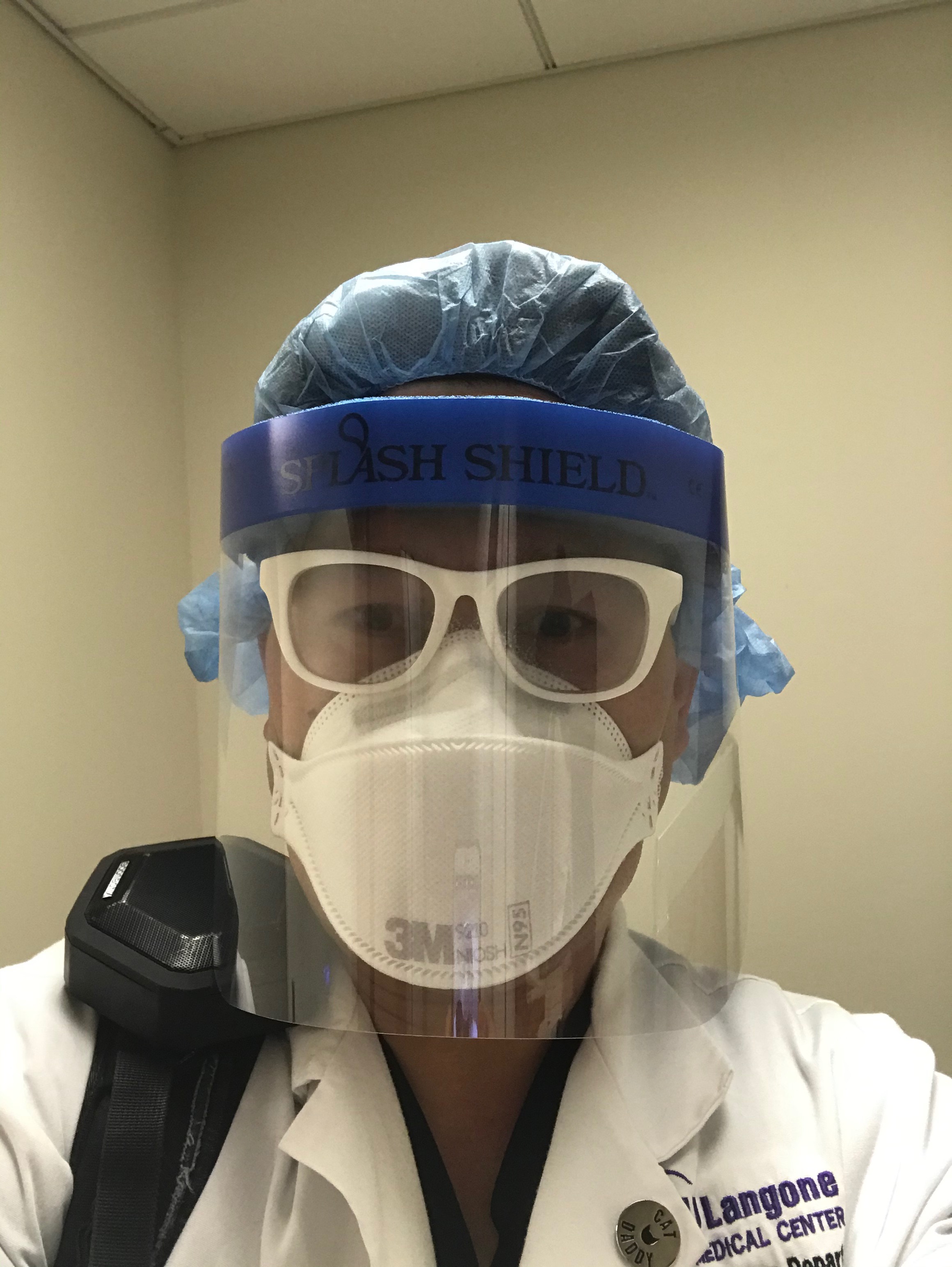

My son is Doctor of Emergency Medicine in New York City. For much of March, the whole of April, and two-thirds of May, all his patients were Covid. He and his co-workers were provided personal protective equipment; but still, he and his co-workers remained in the midst of the illness. Friends asked me to thank him for his contribution, and when I did, he said, “I get paid for my work.” The media referred to his kind of position as front-line and said we’re in a war. It’s now commonplace to call a person in my son’s shoes a hero.

But the virus isn’t at war with us. It doesn’t hate us and we’re not its enemy. The Given Circumstances are, it’s attracted to us and wants to be our guest; it aims to replicate and we’re the chosen place for replication. The Rising Action of this play called Coronavirus is its pandemic spread and the Peak entails huge misfortunate. We don’t yet know the ending.

When I heard the word “hero” being circulated, I thought of a Bertolt Brecht passage that’s stayed with me all my life, and I sent my son a message:

Dear Sonshine,

People say you are a hero. I’m not fond of the word and how it’s used. It was the theatre that taught me why. In Brecht’s play The Life of Galielo, when Galileo recants his scientific discoveries to save his very life, Galileo’s student, so disappointed in his teacher, says to him, “Unhappy is the land that has no heroes.” Galileo replies, “Unhappy is the land in need of heroes.”

I think of you as a fine doctor, and exceptional, who lately, more than ever, has been ongoing called to extraordinary work that you’ve performed with discipline and grace. I don’t think of you as a hero.

Love, Mom

I stay home these days except for walks and hikes. Out there, I notice how elements of theatre have taken hold and we are the players. Without a director, we stage ourselves, keeping 6 feet apart. Some of us are ignorant of the breadth of 6 feet, or possibly we choose to play the role of provocateur or libertarian or villain. For my part, when hiking a rail trail in the Hudson Valley, if someone comes overly-near it feels like a fellow-actor messing up the blocking. I find myself going off-trail into the woods or a creek, as if being swept into the wings. But most hikers move over to their edge of the path with a wave or a nod or even a few words of dialog. Scarves and masks are regular features among our repertoire of elements, and sometimes gloves as well, resulting in altered faces and hands. Our faces have changed, and what will we look like when this particular production has completed its run?

To close this reflection, let us return to Waiting for Godot.

Vladimir: Let us not waste our time in idle discourse! (Pause. Vehemently.) Let us do something, while we have the chance! It is not every day that we are needed. Not indeed that we personally are needed. Others would meet the case equally well, if not better. To all mankind they were addressed, those cries for help still ringing in our ears! But at this place, at this moment of time, all mankind is us, whether we like it or not. Let us make the most of it, before it is too late! Let us represent worthily for once the foul brood to which a cruel fate consigned us! What do you say? (Estragon says nothing.)

Who would have thought that Vladimir’s exhortation could have become more ironic and more touching than it already was?