Start with life. She was lively and if I were to give her a Bodhisattva name it would be Playful Generosity. Her this-world name was Sally Curley. She volunteered on every one of the 19 theatre productions I directed at Villanova University over the years, fulfilling every task from patch panel operator to stage manager. During the run of Ice Cream by Caryl Churchill in 1991, as sound board operator, Sally inadvertently let a tape play out to where an unexpected unwanted Frank Sinatra song came blasting through the speakers. Seth Pendleton was on stage in the role of a London East End punk person. Looking toward the sound booth, as if to an upstairs neighbor, he shouted, “Shut the fuck up,” at which point Sally threw herself bodily on the tape deck and Frank Sinatra stopped.

Every night during the 2-week run of Caryl Churchill’s Fen, Sally reburied potatoes in the dirt floor of the set so the actors could potato-pick anew the next day in performance. The potato-burying made for a messy task and it was the least of how Sally Curley benefited my work across 30 years.

I sometimes slept over at Sally’s house near Villanova during a tech weekend when I was too tired to drive to my place in the city. Her taste was Early American, and there were dolls, some almost life-size, propped on chairs and perched on the sofa. She had literally a roomful of birds that she talked to and one of them, Lucy the cockatiel, talked back. After leaving Villanova and moving from Pennsylvania, I stayed in Sally’s guest room on occasion on return visits. When she developed Parkinson’s and began to divest of material things, she gave me a matching boy and girl doll costumed like characters in a Victorian play.

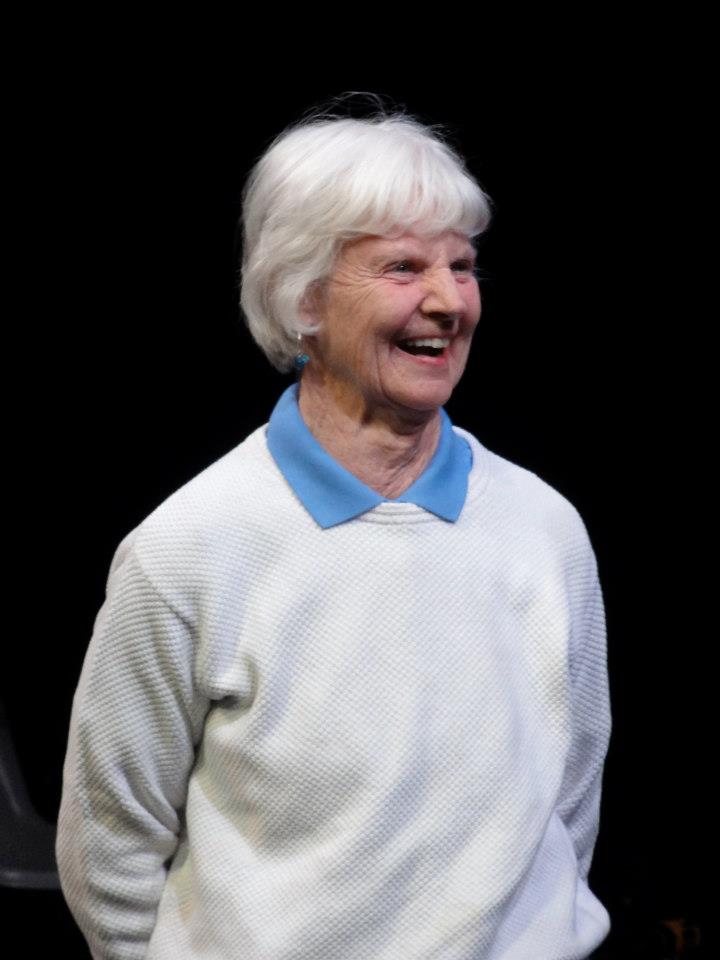

Sally

As the disease progressed, the medication caused Sally instability of memory and motion. She started falling. On one visit I noticed marks on her arms and bruises on her face. I mentioned the cane she wasn’t using and asked about a walker. She said, “I’d rather fall than use a walker.” I said, “It’s up to you.” Next came hallucinations. Sally knew she was hallucinating, and yet to her the hallucinated people looked and sounded entirely present, like visitors. The last time I stayed at Sally’s house, she said the hallucinations sometimes invited her outside and she’d go. Sally’s children moved her to a care-facility. She’d been found at night, fallen in the street.

I last saw Sally at her apartment in the nursing home. She pointed across the room: “There are a lot of people sitting over there on the bed. I see them. They’re really there.” She knew they weren’t visible to me. She knew they weren’t actually there, and she also knew they were there. How was Sally’s hallucination less real than I standing next to her, or how was I more real than the people on the bed?

Whatever we see, to a significant extent, our mind is making up. What we think we are seeing, and the way we see, can be a product of, say, our projections or Parkinson’s, or ignorance. Atisha said it well: “Regard all phenomena as dreams.” Although we may like to consider in this moment that objects and people are solid, in the next moment they are already a passing memory. Is anything fixed, is anything unchanging, is anything substantial ever really happening? It seems that for the most part, we are as if hallucinating.

In her middle years, Sally had worked at a day-care center where her special delight was storytelling. That’s what drew her to the theatre – the stories, the comedies, tragedies and tragicomedies played out on stage; and the scary funny accidents happening in rehearsal and performance. Fiction stories and actual stories, both kinds were real to her. That’s why, I think, for Sally hallucination was not a form of suffering. It was a form of story — a manifestation of imagination, just like theatre.

Me and Sally backstage

In October of 2019 Sally fell backwards in the kitchenette of her nursing-home room. She hit her head and entered a coma. I suggested to Rose Malague, a former graduate student at Villanova who’d roomed at Sally’s house, that it would be a great kindness to go to the hospital and tell Sally where she was and what had happened to her. I believed she’d hear Rose and recognize her voice. And I asked her to deliver a message: “Joanna loves you and is sorry she’s not here to give you notes for backstage.”

At sunset I went for a walk. I talked to Sally for a while, thanking her. Then I gave a final stage direction: “Go for the light, Sally, no matter what,” and then I cried.

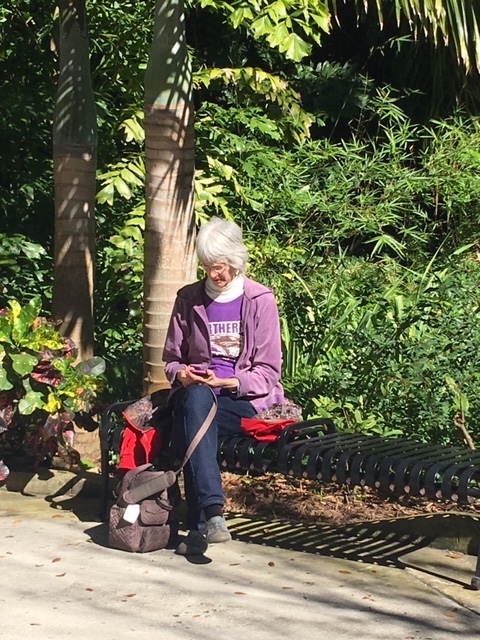

“Sally” at Sunken Gardens

Coda: Several months later, I was in St. Petersburg, FL, visiting the Sunken Gardens, home of 21 shrimp-color flamingos and an array of vibrant parrots, macaws and kookaburras. On my way to the exit, I noticed, far from the other birds, a cage with a single cockatiel. She was Mindy, all white, the only cockatiel at Sunken Gardens and the only bird without color. Sally came to mind and her cockatoo Lucy — though of grey plumage with yellow. Barely audibly, in the presence of Mindy, I said, “Hi Lucy. Hi Sally.” Then I walked 5 steps to the end of the pathway and there in the space in front of me was a white-haired woman on a bench. I thought I was in a dream where Sally hadn’t died, or I was hallucinating, or it was Sally framed within the palm-frond foliage of the Sunken Gardens.